Our industry is engaged in an important dialogue to improve sustainability through ESG transparency and industry collaboration. This article is a contribution to this larger conversation and does not necessarily reflect GRESB’s position.

As the reality of climate change starts to set in, the building industry is realizing that it is responsible for a significant portion of human emissions on the planet. With buildings currently responsible for 39% of global carbon emissions, decarbonizing the sector is one of the most cost-effective ways to mitigate the worst effects of climate breakdown. The built environment sector has a vital role to play in responding to the climate emergency. More scrutiny is now given to the whole lifecycle of buildings to see where emissions can be further reduced. Some of these emissions are from operating buildings and those we have known about for a long time, but there is another side of buildings and climate change that hasn’t been the focus of attention until more recently. And that is embodied carbon.

What is embodied carbon?

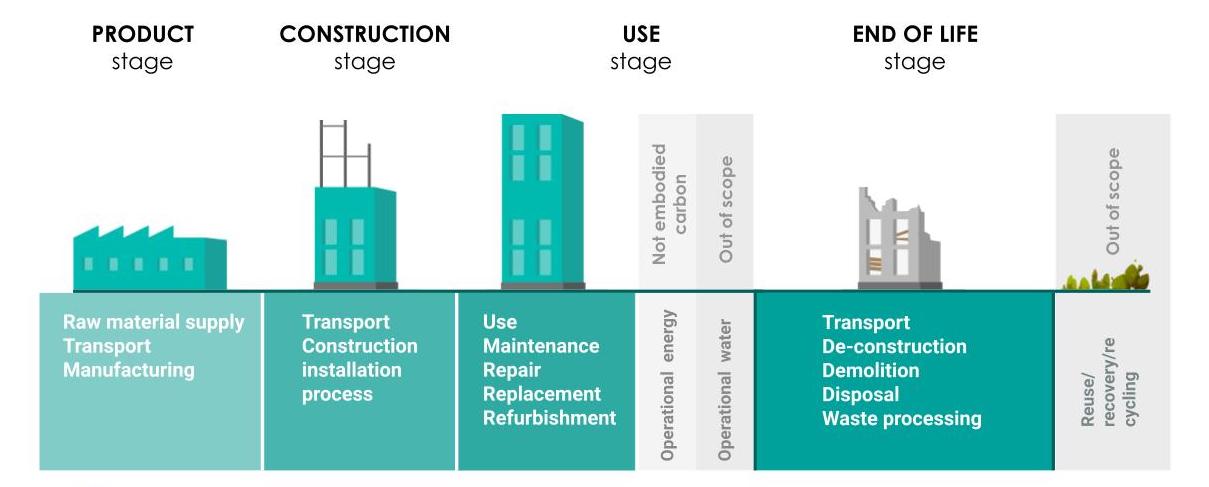

What is embodied carbon, and why is it a significant challenge for the real estate and construction sector? According to the European Commission (2020), embodied carbon relates to “the greenhouse gas emissions associated with the non-operational phase of a project, namely the emissions released through extraction, manufacturing, transportation, assembly, maintenance, replacement, deconstruction, disposal, and end of life aspects of the materials and systems that make up a building (cradle to grave).” Embodied carbon is everywhere in the building lifecycle.

According to Architecture 2030, “globally, embodied carbon is responsible for 11% of annual GHG emissions and 28% of building sector emissions. As operational energy efficiency increases, the impact of embodied carbon emissions in buildings will become increasingly significant.” This suggests that the net zero 2050 goal is not achievable without action on embodied carbon. And since the embodied carbon footprint is so significant, learning how to work with these numbers is essential.

Why tackle embodied carbon and where to focus?

Optimizing the carbon footprint of a building over its lifetime involves striking a balance between minimizing embodied carbon and reducing operational emissions. Unlike operational emissions, which are the amount of carbon emitted during the operational or in-use phase of a building, the impact of embodied carbon occurs at the time of construction and renovation and can’t be reduced afterwards. This means that embodied carbon will account for around 50% of built environment emissions by 2035, while operational emissions from buildings will decrease thanks to the growing global environmental awareness and the current regulatory framework, which is pushing real estate players to reduce their operational emissions. But this often requires renovation work and, therefore, the addition of embodied carbon. Yet the global urban population is set to grow by 2.75 billion by 2060, and the required new buildings to host them will emit over 100 gigatons of embodied carbon. This suggests that if no action is taken to address embodied carbon, the European 2050 net-zero goal will not be achieved.

Where are we in terms of regulations?

The built environment sector has a vital role to play in responding to the climate emergency, and addressing embodied carbon is a critical and urgent focus. The next challenge to overcome, especially for new construction, is implementing an effective net-zero strategy.

EU legislation has focused on reducing greenhouse gas emissions associated with the energy needed to heat, cool, and power a building. Although a lot remains to be done to cut down embodied carbon, it has moved a lot higher up the agenda for industry and government. Only five EU countries — Denmark, Finland, France, the Netherlands, and Sweden — have introduced regulation on whole-life carbon emissions, addressing both operational and embodied emissions.

One of the best examples to date is the RE2020 in France which entered into force in January 2022. The regulation introduces new building requirements that aim to reduce emissions from building materials over the life of the building, including demolition. RE2020 goes beyond reducing and decarbonizing a building’s energy consumption – it also aims to promote sustainable, low-carbon building materials. It defined construction thresholds for single and collective housing by 2031 as follows:

- For single housing, 640 kg CO2-eq/m2/year of embodied carbon emissions in 2022 to 415 kg CO2-eq/m2/year in 2031.

- For collective housing, 740 kg CO2-eq/m2/year of embodied carbon emissions in 2022 to 490 kg CO2-eq/m2/year in 2031.

This regulation is an important step towards contributing to the national goal of decarbonizing all sectors by 2050 in France.

Furthermore, since January 2022, developers in Sweden must calculate the embodied carbon emissions of new buildings before submitting them to the government in order to receive the final building permit. According to the Climate Disclosure Act for new buildings, these calculations must cover the so-called direct embodied emissions, taking into account the initial production of materials and the different construction phases of a building’s life cycle.

Companies that start measuring embodied carbon in their projects now will improve the skills of their staff, induce a culture change in the sector, and get ahead of upcoming inevitable regulations on embodied carbon.

A European challenge

There are hard choices to be made about whether new constructions or operationally efficient renovations are most effective in reducing overall carbon emissions. But given that 80% of the 2050 building stock is already standing, the need to reduce the impact of operational emissions by retrofitting existing buildings is clear. However, the real estate sector can no longer renovate without considering the embodied carbon emitted during these renovation strategies. Indeed, the embodied carbon is increased during renovations done in order to reduce operational emissions that are far too high.

Thus, the European challenge is to continue to reduce the carbon footprint of new buildings on the one hand, and on the other hand, to carry out low-embodied-carbon works involving a strong reduction in operational emissions to reduce emissions over the whole life cycle of existing buildings.

On December 15, 2021, the European Commission adopted a major revision of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) as part of the ‘Fit for 55’ package. The EPBD requires member states to lower the energy consumption of buildings and requires all new buildings from 2021 onwards (public buildings from 2019) to be nearly zero-energy buildings (NZEB). The proposed measures take into account, in particular, the increase in renovation rates, especially for the least efficient buildings in each Member State. They will modernize the building stock, making it more resilient and accessible.

Initially, the draft revision of the EPBD focused only on energy performance, with requirements that addressed only emissions during the operational phase of buildings. The European Environmental Bureau (EEB) and the Environmental Coalition on Standards (ECOS) advocated for the inclusion of life cycle emissions. Indeed, the proposed revision of the directive now refers to the whole life cycle, which is real progress. The ongoing negotiations on the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD), expected to conclude in summer 2023, represent a unique opportunity to broaden the narrative on building decarbonization to include the full range of building emissions and put an actionable framework into place. It could change the way embodied carbon is addressed at a European scale.

Embodied carbon is rising up the agenda, although regulators from different European countries are not on the same page. It raises increased attention from the building sector. The current and upcoming work of some European countries will hopefully encourage significant initiatives over the next several years.

This article was written by Clémentine Tanguy, Content Manager at Deepki.

References

- https://gresb-prd-public.s3.amazonaws.com/2022/2023+Standards/List+of+2023+Changes+GRESB+Real+Estate

- Waldman, B., Huang, M. et Simonen, K. (2020). Carbone incorporé dans les matériaux de construction: un cadre pour quantifier la qualité des données dans les EPD. Bâtiments et villes, 1(1), 625–636. EST CE QUE JE

- https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/the-race-to-track-and-eliminate-embodied-emissions-from-buildings/

- https://fs.hubspotusercontent00.net/hubfs/7520151/RMC/Content/EU-ECB-5-all-in-one-report.pdf

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.22300/1949-8276.11.1.174

- https://www.lowcarbonmaterials.com/blog/embodied-carbon-the-new-challenge-for-builtenvironment-regulation

- https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5803/cmselect/cmenvaud/643/report.html

- https://worldgbc.org/advancing-net-zero/embodied-carbon/

- https://www.agora-energiewende.de/en/publications/re2020-in-france/

- https://ecostandard.org/news_events/checklist-for-a-successful-epbd-recast/

- https://www.eceee.org/all-news/news/the-eu-needs-a-whole-life-carbon-roadmap-for-buildings/