Our industry is engaged in an important dialogue to improve the efficiency and resilience of real assets through transparency and industry collaboration. This article is a contribution to this larger conversation and does not necessarily reflect GRESB’s position.

Green financing hidden in plain sight

Discussions around sustainable development frequently focus on green bonds, climate funds, and ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) performance indicators. Many of the most effective financial instruments are already integrated into local policy frameworks but need legal alignment to address current infrastructure demands.

This was the issue in Texas. For many years, developers creating next-generation communities have contemplated using innovative green infrastructure like geothermal HVAC but have not had clear access to public funding options typically available for roads, water, and drainage. House Bill 4370, created and supported by the TexasTENs initiative, was passed unanimously by both chambers and presents a legislative model that provides clear access to these tools for environmentally sustainable and efficient development.

The bill didn’t create a new subsidy or financial product. It amended local codes to explicitly allow special-purpose districts to fund geothermal water conveyance systems, using financing tools already available to developers. The result is a replicable model, not only for Texas, but one that serves as a roadmap for other states to follow on how to unlock creative financing mechanisms to enable green infrastructure projects to get done on a large scale.

A simple legal adjustment with broad implications

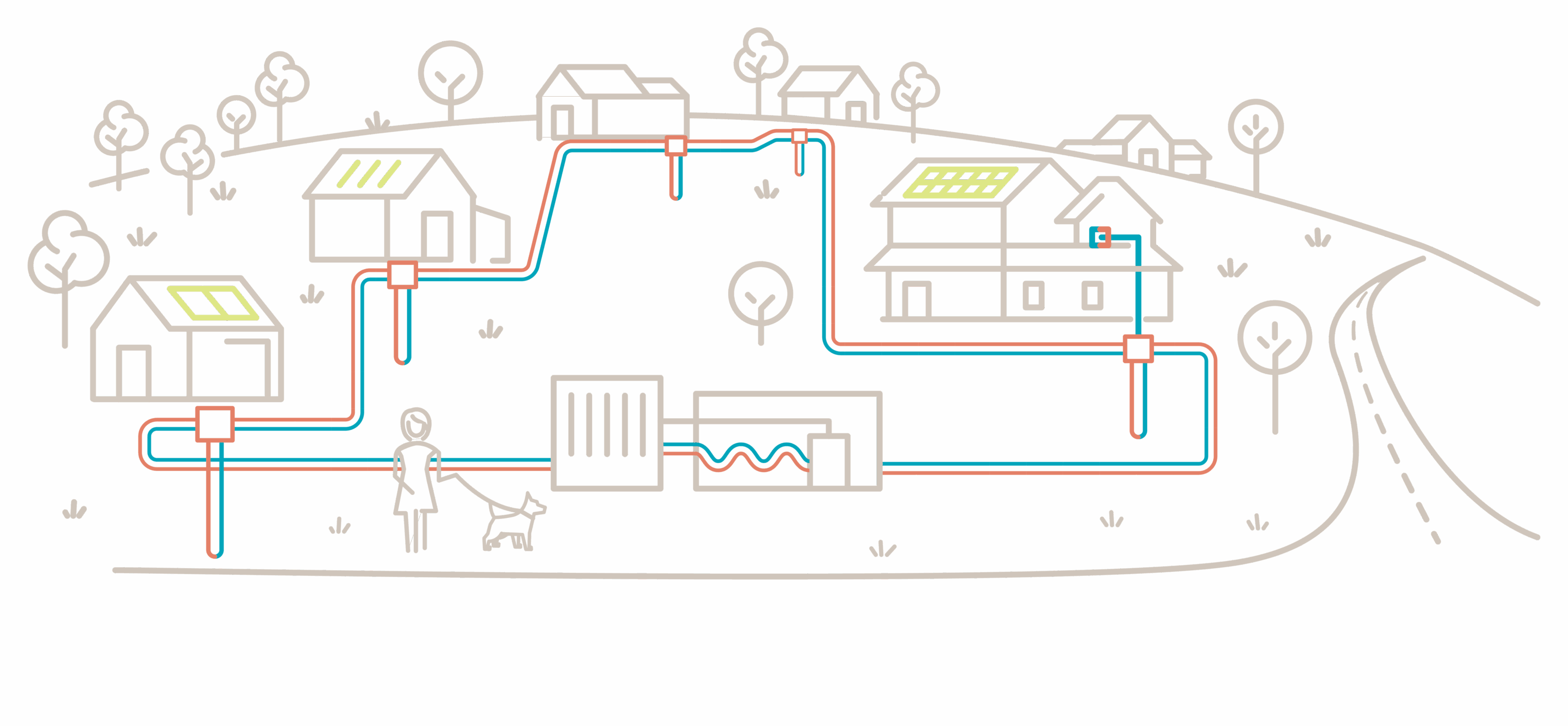

Under the definition of Thermal Energy Networks (TENs), closed-loop geothermal systems circulate water underground to deliver heating and cooling across multiple buildings. They reduce peak electricity loads, cut emissions, and operate efficiently over decades. However, despite their proven performance, adoption has been slowed by outdated legal definitions in public infrastructure statutes.

In Texas, various special-purpose districts—Public Improvement Districts (PIDs), Municipal Utility Districts (MUDs), Tax Increment Reinvestment Zones (TIRZs), and others—manage and finance infrastructure through the issuance of bonds, assessments, and fees. Before HB4370, these entities could finance water pipes or sewer lines, but not the geothermal equivalents.

HB4370 expanded their authority. With its passage, these districts can now build, finance, and maintain geothermal water conveyance systems as part of their standard infrastructure portfolios. The bill also clarified cost responsibilities in municipal management districts, ensuring transparent treatment of geothermal assets during relocations or modifications.

For developers: Unlocking more than infrastructure

The impact is practical. Developers can now design communities around shared geothermal systems and access familiar financing mechanisms to fund them. Doing so removes reliance on fragmented private arrangements and allows for long-term integration with public services.

In Whisper Valley, a large-scale residential development located outside Austin, Texas, homes are connected to a shared underground geothermal loop that provides heating and cooling through ground-source heat pumps. This system operates similarly to other district utilities, such as water or sewer infrastructure, but circulates thermal energy through a closed-loop network. Prior to the passage of HB4370, special districts in Texas lacked apparent authority to finance this kind of infrastructure, despite its alignment with public community and utility goals. The bill resolved that gap, enabling the use of standard public financing tools for thermal energy systems in qualifying developments.

Lessons for broader application

The relevance of this policy extends beyond the state of Texas. Most U.S. states allow special districts to finance infrastructure, yet their legal definitions may still reflect the technology of decades past. Updating this language doesn’t require new money; only precision is needed.

Developers, utilities, and municipalities elsewhere can apply similar strategies. First, review the existing district law language to determine if your desired green infrastructure is explicitly permitted. This could include geothermal or thermal energy systems or other solutions like microgrid component infrastructure. Then, work with legal and legislative teams to draft updates. Early engagement with policymakers and alignment across technical and financial stakeholders is key.

A strategic opportunity for GRESB members

GRESB participants evaluating portfolios through a sustainable lens should consider how clarity on specific public financing options influences and unlocks possible financing options. Projects with access to public infrastructure funding for low-carbon systems now have another tool, which could be the reason they are able to get done.

This is not only a story about Texas. It is a reminder that public and private alignment through legislative action can be a powerful tool. Public financing options, when properly defined, can support infrastructure that meets both environmental and economic goals.

Green financing does not always necessitate the creation of new instruments. Sometimes, it means making the tools we already have available to the infrastructure we now need. HB4370 serves as a case study in how policy can quietly, yet significantly, shift what is possible on the ground. For developers, investors, and governments alike, the path to scalable sustainability may start with a line of text in the local codebook.

This article was written by Zachary Turov, Business Development Manager at EcoSmart Solution. Learn more about EcoSmart Solution here.