Our industry is engaged in an important dialogue to improve the efficiency and resilience of real assets through transparency and industry collaboration. This article is a contribution to this larger conversation and does not necessarily reflect GRESB’s position.

Climate change isn’t just a future threat; it’s already reshaping the real estate market. From flooded homes and rising insurance costs to overheating buildings and shifting buyer demand, physical climate risks are impacting property valuation, investment decisions, and tenant satisfaction. The projected financial impact on real estate from physical risks, as modelled by S&P, is USD 54 billion by 2050. To stay ahead, real estate must embed climate resilience into every stage of the property lifecycle, from acquisition, planning, and design to construction, operation, and eventual disposal. Resilient buildings are not only safer, they’re also more desirable, more valuable, and better equipped to withstand the challenges ahead.

This piece explores how physical climate risk and resilience opportunities can be factored into each stage of the property lifecycle and why doing so is critical for real estate’s long-term value and viability.

What are physical climate risks?

Physical climate risks relate to the financial risks and losses that can arise from the adverse effects of climate change. Physical climate risks come in two forms: acute event-driven hazards (weather events that climate change turns more extreme) like floods and wildfires, which cause immediate damage and disruption, and chronic hazards like rising temperatures and sea level rise that slowly erode property value and livability over time.

Implications of physical climate risks for the real estate sector

Physical climate risks (both acute and chronic) have the following implications for the real estate sector:

- Damage and repair costs—Climate change presents serious challenges to the real estate sector, with events like floods, wildfires, heatwaves, and droughts becoming more frequent and severe, leading to increased damage costs. According to Aon, since the start of 2025 alone, natural and climate-related disasters have already cost at least USD 162 billion in economic damages, with projections suggesting this figure could rise significantly by the end of the year. This included both insured (USD 100 billion) and uninsured (USD 62 billion) losses largely driven by Los Angeles wildfires and severe storms across the US.

- Impact on valuations—The property market is undergoing a subtle but significant shift. Climate change, once seen as a distant concern, is now influencing how buyers assess value, where investors place capital, and which properties are seen as future-proof. Physical climate risks like flooding, storms, heatwaves, and coastal erosion can damage buildings, disrupt communities, and drive up insurance and maintenance costs. Over time, these risks reduce property values, make homes harder to insure or mortgage, and shift buyer demand toward more resilient, future-proof locations. In England, around eight million properties, or one in four, could be at risk of flooding by 2050, according to the Environment Agency. All of these properties could be at risk of declining value from reduced insurance availability and affordability, changing buyer behaviors, and risk-averse lending practices.

- Investor expectations—As climate impacts become more visible, the property market is responding, not just with new building standards or mandatory disclosures, but with a shift in mindset. Climate resilience is no longer a bonus feature; it’s becoming a baseline expectation. The increasing incorporation of climate risk and resilience in reporting and disclosures such as GRESB criteria, BREEAM assessments, and ISSB reflects this change. These frameworks aren’t just about ticking boxes; they’re pushing the industry to measure, report, and act on climate risks in a way that influences investment decisions, asset performance, and long-term value.

- Tenant satisfaction—Tenant satisfaction is a key indicator of a property’s long-term viability. As physical climate risks like flooding and overheating become more common, tenants are increasingly prioritizing comfort, safety, and reliability. Buildings that can’t cope with extreme weather or rising energy costs risk higher turnover, lower occupancy rates, and reputational damage.

Opportunities for climate resilience across the property lifecycle

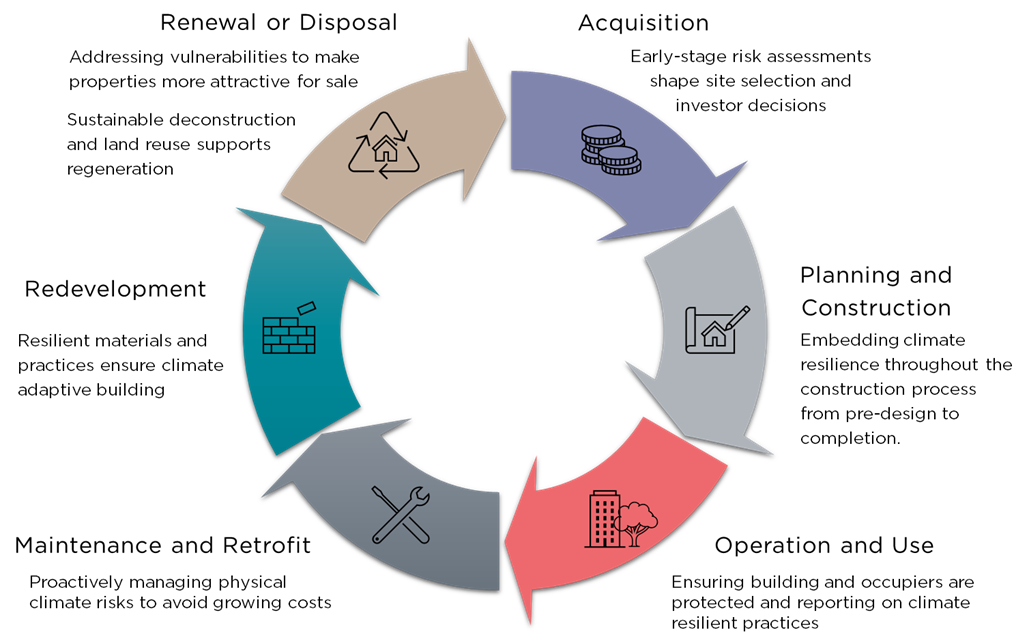

Climate resilience is essential across every stage of the property lifecycle. From acquisition, planning, and construction to operation, maintenance, and eventually redevelopment and/or disposal, each stage of the property lifecycle presents opportunities to reduce physical climate risks and increase long-term value and resilience. The following outlines how physical climate risks are considered and can be addressed at each stage.

Source: Savills

Acquisition: identifying value enhancement strategies

Physical climate risks are increasingly being assessed within acquisition due diligence processes as a way to understand the potential impacts of climate change on the value and long-term viability of a property before purchase.

An assessment of physical climate risks for acquisition due diligence includes:

- Identification of the potential physical climate hazard exposures (acute and chronic) based on the location of a property. Best practices assess hazards over multiple time periods, using climate model projection outputs over a range of scenarios (e.g., IPCC RCP and SSP scenarios), to understand how resilient a real estate asset is to climate change impacts over its expected lifecycle.

- Evaluation of the existing state of the building to find any vulnerabilities to hazards identified to be potentially material based on the property (or site) location.

Whilst physical climate risk assessments can influence investor decisions and, in the case of land purchases for new site development, influence site selection, they can also inform strategies to enhance property resilience that will improve the longevity and value of a building.

Planning and construction: building climate-resilient properties

During the planning and construction of new buildings, physical climate risk assessments can be used to inform building specifications with resilient design, materials, and infrastructure, which can withstand the impacts of a changing climate.

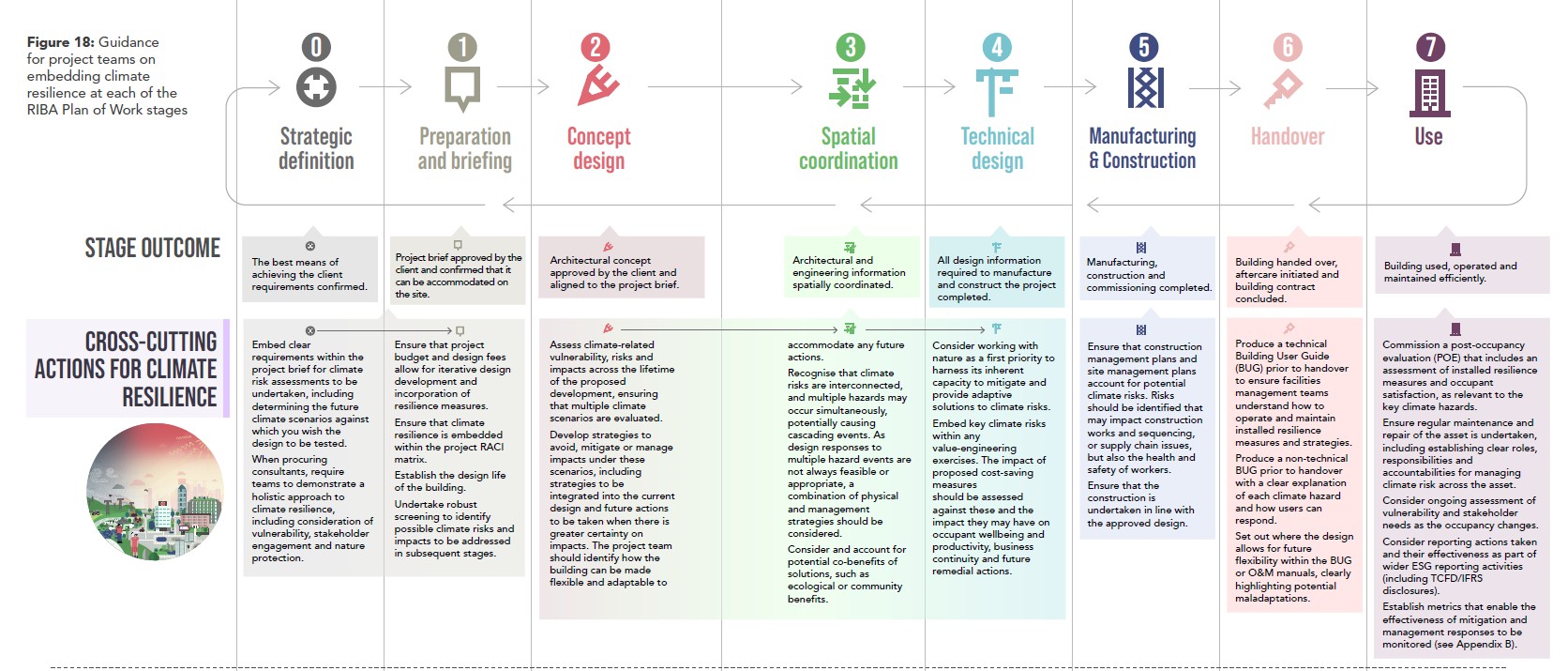

The challenge is ensuring physical climate risk is fed into the multi-phased process of a building construction project, as well as ensuring all members of the project are aligned on climate resilience objectives. The UK GBC Climate Resilience Roadmap provides guidance on how to embed climate resilience across the eight stages of the RIBA plan of work (see graphic below). The approach varies by climate hazard (beyond the cross-cutting aspects shown in the image below); however, broadly speaking, the roadmap recommends:

- Identifying possible physical climate hazards at the project brief stage

- Assessing vulnerabilities and developing adaptation strategies to address physical climate risks during the design stages, whilst encouraging the use of nature-based solutions and

- Ensuring physical climate risks are accounted for in site management plans during the construction stage and building user guidance during the handover and occupation stage

Embedding climate resilience at each of the RIBA Plan of Work stages, UK Climate Resilience Roadmap.

Operation and maintenance: reporting on physical climate risk management

For properties at the operational stage of their lifecycle, climate resilience has shifted from a value-add to a fundamental requirement, and the increasing incorporation of climate risk and resilience in reporting and disclosures reflects this change.

At the entity level, climate resilience is increasingly being added to reporting benchmarks such as GRESB, where the Climate Resilience Indicator encourages wider adoption of climate resilience measures, informed by physical climate risk assessment and scenario analysis.

At the property level, building certifications such as BREEAM require evidence of building-level practices to manage potential exposures to physical climate risks. As climate change impacts are increasingly being felt, building owners or site management teams are seeing unexpected cost allocations for interventions or repairs related to physical climate risks within service charge budgets and/or CapEx and OpEx plans. Proactively assessing and managing physical climate risks is imperative to avoid growing costs.

Renewal or disposal: proactive risk reduction to enhance market appeal

Physical climate risk and resilience at the renewal or disposal stage is about how to reduce risk before it is transferred to a new owner. Addressing physical climate risks involves proactively addressing any vulnerabilities or improving asset resilience to make a property more attractive for sale and improve value, circling back to the principles of the acquisition stage.

Conclusion

There is increased prevalence of factoring in physical climate risk assessments and developing strategies for climate resilience across all stages of the property lifecycle. Regulations such as the EU Taxonomy have explicit criteria for physical climate risk assessments and implementation of climate adaptation solutions across multiple real estate activities: construction of new buildings, renovation of existing buildings, and the acquisition and ownership of buildings. There is also increased standardization—the Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC) Physical Climate Risk Appraisal Methodology (PCRAM 2.0) is a cross-industry-led guidance on integrating physical climate risks into real estate investment decision-making and encourages the use of proactive physical climate risk assessment and management to ensure long-term asset performance.

The need for climate resilience and future-proofing real estate has never been greater.

This article was written by Sarah Brayshaw, Principal Climate Risk and Resilience Consultant and Megan Steven, Senior Climate Risk and Resilience Consultant at Savills. Learn more about Savills here.